Some time back I posted a piece titled Numbering Those On the Ranch, exploring the concept of what missiologist Alan Hirsch refers to as a “centered-set” metric for evaluating a church. More recently I stumbled across a post by Bob Thune, of Coram Deo Church in Omaha, explaining his understanding of Centered-Set verses the more traditional Bounded-Set metric. I appreciated what Thune had to say, so I wanted to post it, even if primarily for my own benefit, as a resource for future use.

***

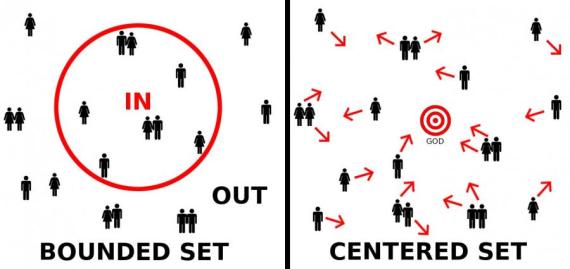

There are two ways of thinking about social groupings: centered-set and bounded-set. These terms come to us from the field of mathematics (set theory). In recent years they’ve been applied more broadly by sociologists and missiologists. The fountainhead of most of this thinking in the Christian church was Paul Hiebert, a missiologist at Fuller Seminary.

Hiebert suggested that our minds categorize people according to either “bounded set” or “centered set” thinking:

Bounded Sets

- … are formed by defining the boundaries – the essential qualities which separate something inside the set from something outside. Heibert’s classic example is “apples.” Either a fruit is an apple, or it isn’t.

- Maintaining the boundary is crucial to maintaining the category.

- Bounded sets are static sets – they don’t change, they only add or lose members.

- The important thing is to “cross the boundary” to be part of the set.

Centered Sets

- … are formed by defining a center. The set is made up of all objects moving toward that center. As an everyday example: “bald men.”

- While a centered set does not focus on the boundary, a boundary does indeed exist. The boundary is clear so long as the center is clear.

- The objects within a centered set are not categorically uniform. Some may be near the center and others far from it, even though all are moving towards the center.

Hiebert asserts that Americans tend to think almost exclusively in bounded-set categories. And this affects our understanding of Christian discipleship. We tend to “stress evangelism as the major task — getting people into the category. Moreover, we… see conversion as a single dramatic event — crossing the boundary between being a ‘non-Christian’ and being a ‘Christian’” (Hiebert, 1978).

Hiebert argues instead for a “centered-set” way of thinking about Christian conversion:

A Christian would be defined in terms of a center—in terms of who is God. The critical question is, to whom does the person offer his worship and allegiance? …Two important dynamics are recognized. First there is conversion, which in a centered set means that the person has turned around. He has left another center or god and has made Christ his center. This is a definite event—a change in the God in whom he places his faith. But, by definition, growth is an equally essential part of being a Christian. Having turned around, one must continue to move towards the center. There is no static state. Conversion is not the end, it is the beginning. We need evangelism to bring people to Christ, but we must also think about the rest of their lives. We must think in terms of bringing them to Christian maturity in terms of their knowledge of Christ and their growth in Christlikeness.

Theologically, I find some aspects of Hiebert’s argument poorly nuanced. He would do well to differentiate regeneration (the invisible, immediate work of the Holy Spirit on the soul, which is in fact a decisive event) from conversion (our experience of that event, which often feels more like a “process” than like a decisive moment). Those who have applied Hiebert’s set theory to individual salvation (Brian McLaren, for instance) have tended to drift in fuzzy doctrinal directions.

But I find Hiebert’s insights immensely helpful when applied to ecclesiology. This is where I first encountered the set-theory rubric, as applied by Alan Hirsch and Michael Frost in their 2003 book The Shaping of Things to Come. Frost and Hirsch argued for viewing the church as a centered set rather than a bounded set. Why not build a church by defining the center rather than patrolling the boundaries? Why not place the gospel of Jesus Christ at the center of the church’s life and practice, inviting everyone to reorient their lives around Him? In this way, we continually invite Christians into deeper and deeper discipleship, while also inviting non-Christians to deal with the claims of Jesus on their lives. As Hiebert himself acknowledges, this does not mean there is no boundary; there is just “less need to play boundary games and to institutionally exclude those who are not truly Christian. Rather, the focus is on the center and pointing people to that center” (Hiebert, 1978).

It is my personal conviction that: a) this is what the New Testament church did (see, for example, Galatians 1:6-9; Colossians 1:6; Romans 1:13-15); b) this is what it truly means to be a “gospel-centered” church; and c) this is the only way to have a truly missional church, where non-Christians are treated with true Christian hospitality AND are regularly being converted to faith in Jesus.