by Tim Keller

THE WORSHIP WARS

One of the basic features of church life in the U.S. today is the proliferation of worship and music forms. This in turn has caused many severe conflicts both within individual congregations and whole denominations. Most books and articles about recent worship trends tend to fall into one of two broad categories.

- “Contemporary Worship” (hereafter CW) advocates often make rather sweeping statements, such as “pipe organs and choirs will never reach people today.”

- “Historic Worship” (hereafter HW) advocates often speak similarly about how incorrigibly corrupt popular music and culture is, and how they make contemporary worship completely unacceptable.

Contemporary Worship: Plugging In?

One CW advocate writes vividly that we must ‘plug in’ our worship in to three power sources: “the sound system, the Holy Spirit, and contemporary culture.” But several problems attend the promotion of strictly contemporary worship.

First, some popular music does have severe limitations for worship. Critics of popular culture argue that much of it is the product of mass-produced commercial interests. As such, it is often marked by sentimentality, a lack of artistry, sameness, and individualism in a way that traditional folk art was not.

Second, when we ignore historic tradition we break our solidarity with Christians of the past. Part of the richness of our identity as Christians is that we are saved into a historic people. An unwillingness to consult tradition is not in keeping with either Christian humility or Christian community. Nor is it a thoughtful response to the post-modern rootlessness which now leads so many to seek connection to ancient ways and peoples.

Finally, any worship that is strictly contemporary will become ‘dated’ very, very quickly. Also, it will necessarily be gauged to a very narrow ‘market niche.’ When Peter Wagner says we should ‘plug in’ to contemporary culture, which contemporary culture does he mean? White, black, Latin, urban, suburban, ‘Boomer,’ or ‘GenX’ contemporary culture? Just ten years ago, Willow Creek’s contemporary services were considered to be ‘cutting edge.’ Today, most younger adults find them dated and ‘hokey.’

Hidden (but not well!) in the arguments of contemporary worship enthusiasts is the assumption that culture is basically neutral. Thus there is no reason why we cannot wholly adapt our worship to any particular cultural form. But worship that is not rooted in any particular historic tradition will often lack the critical distance to critique and avoid the excesses and distorted sinful elements of the particular surrounding, present culture. For example, how can we harness contemporary Western culture’s accessibility and frankness, but not its individualism and psychologizing of moral problems?

Historic Worship: Pulling Out?

HW advocates, on the other hand, are strictly ‘high culture’ promoters, who defend themselves from charges of elitism by arguing that modern pop music is inferior to traditional folk art. But problems also attend the promotion of strictly traditional, historic worship.

First, HW advocates cannot really dodge the charge of cultural elitism. A realistic look at the Christian music arising from the grassroots folk cultures of Latin America, Africa, and Asia (not commercially produced pop music centers) reveals many of the characteristics of contemporary praise and worship music–simple and accessible tunes, driving beat, repetitive words, and emphasis on experience. In the U.S., an emphasis on strictly high culture music and art will probably only appeal to college educated elites.

Second, any proponent of ‘historic’ worship will have to answer the question – ‘whose’ history? Much of what is called ‘traditional’ worship is rooted in northern European culture. While strict CW advocates bind worship too heavily to one present culture, strict HW advocates bind it too heavily to a past culture. Do we really believe that the 16th century Northern European approach to emotional expression and music (incarnate in the Reformation tradition) was completely Biblically informed and must be preserved?

Hidden (but not well!) in the arguments of traditional worship advocates is the assumption that certain historic forms are more pure, Biblical, and untainted by human cultural accretions. Those who argue against cultural relativism must also remember the essential relativity of all traditions. Just as it is a lack of humility to disdain tradition, it is also a lack of humility (and a blindness to the ‘noetic’ effects of sin) to elevate any particular tradition or culture’s way of doing worship. A refusal to adapt a tradition to new realities may come under Jesus’ condemnation of making our favorite human culture into an idol, equal to the Scripture in normativity (Mark 7.8-9) While CW advocates do not seem to recognize the sin in all cultures, the HW advocates do not seem to recognize the amount of (common) grace in all cultures.

Bible, Tradition, and Culture

At this point, the reader will anticipate that I am about to unveil some grand ‘Third Way’ between two extremes. Indeed, many posit a third approach called “Blended” worship. But it is not so simple as that. My major complaint is that both sides are equally simplistic in the process by which they shape their worship.

CW advocates consult a) the Bible and b) contemporary culture, while HW advocates consult a) the Bible and b) historic tradition. But we forge worship best when we consult a) the Bible, b) the cultural context of our community, and c) the historic tradition of our church. 10 The result of this more complex process will not be simply a single, third “middle way.” There are at least nine worship traditions in Protestantism alone. 11 That is why the book you are reading provides examples of culturally relevant worship that nonetheless deeply appreciates and reflects its historic tradition.

This more complex approach is extremely important to follow. The Bible simply does not give us enough details to shape an entire worship service. When the Bible calls us to sing God’s praises, we are not given the tunes nor the rhythm. We are not told how repetitive the lyrics are to be or not to be, nor how emotionally intense the singing should be. When we are commanded to do corporate prayer, we are not told whether those prayers should be written, unison prayers or extemporary prayers. 12 So to give any concrete form to our worship, we must “fill in the blanks” that the Bible leaves open. When we do so, we will have to draw on a) tradition, b) the needs, capacities and cultural sensibilities of our people, and c) our own personal preferences. Though we cannot avoid drawing on our own preferences, this should never be the driving force. (cf. Romans 15.1-3) Thus, if we fail to do the hard work of consulting both tradition and culture, we will – wittingly or unwittingly – just tailor music to please ourselves.

THE SEEKER-SENSITIVE WORSHIP MOVEMENT

Sally Morgenthaler’s interview with young pastors (Chris Seay, Mark Driscoll, Ron Johnson, Doug Pagitt, Clark Crebar) in Worship Leader (May/June 1998) “Authentic Worship in a Postmodern Culture” and Fernando Ortega’s interview in Prism in Nov/Dec 1997 are indications of some major cracks in the foundation of evangelical assumptions about what kind of services will reach ‘secular’ people.

The crisis (that is here? coming?) in the church growth movement due to the fact that the attack on seeker-sensitive worship is coming from inside, that is, from the pastors of fast growing ‘mega-churches’ (though the name and category is eschewed) filled with under-30’s. These pastors claim that the Willow Creek inspired services supposedly adapted for the unchurched were calibrated for a very narrow and transitory kind of unchurched person: namely, college educated, white, Baby Boomers, suburbanites. The increasingly multi-ethnic, less rational/word-oriented, urban oriented and more secular generations under the age of 35 are not the same kind of ‘unchurched’ people. The critique is that Willow Creek ‘over-adapted’ to the rational, a-historical ‘high modern’ world-view.

The younger pastors say that Willow Creek services do several things that alienate the seekers of their generations:

a) It removed transcendence from its services by utilizing light, happy music and tone, complete accessibility of voice, using dramatic sketches that create a nightclub or TV-show atmosphere. But their generations hunger for awe.

b) It ditched connection to history and tradition and went completely contemporary in all cultural references, from sermon illustrations to decoration to antiseptic ‘suburban mall/office building’ setting.But their generations hunger for rootedness, and love a pastiche of ancient and modern.

c) It emphasized polish and technical excellence and slick professionalism and management technique, while their generations hunger for authenticity and community rather than programs.

d) It emphasizes rationality and practical ‘how-to’ maps, while their generations hunger for narrative and the personal.

A SOLUTION: EVANGELISTIC WORSHIP

Two models, with problems

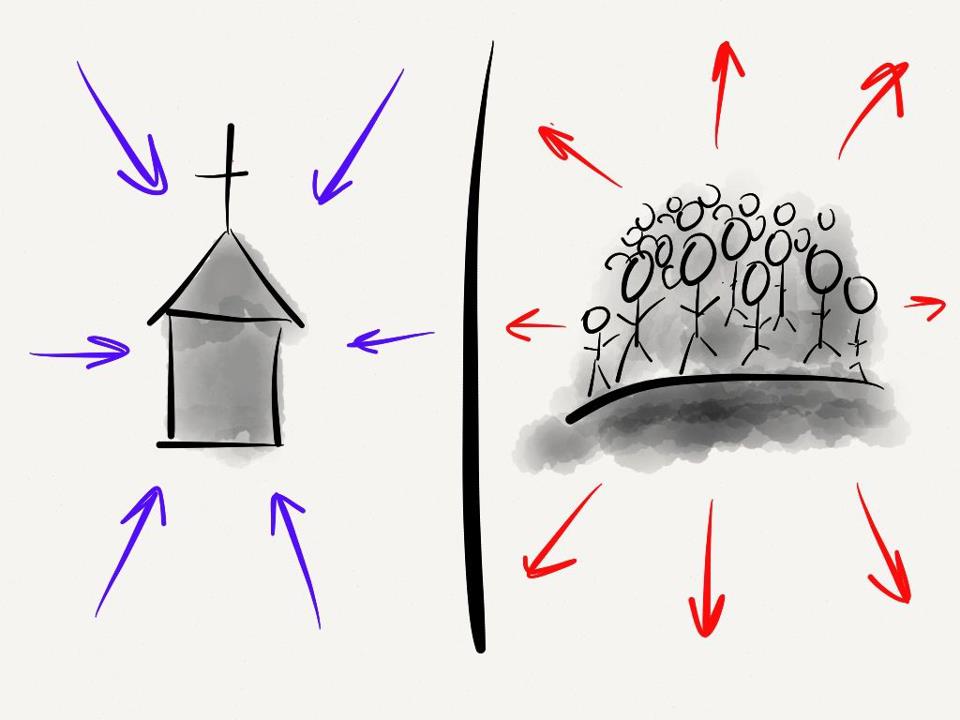

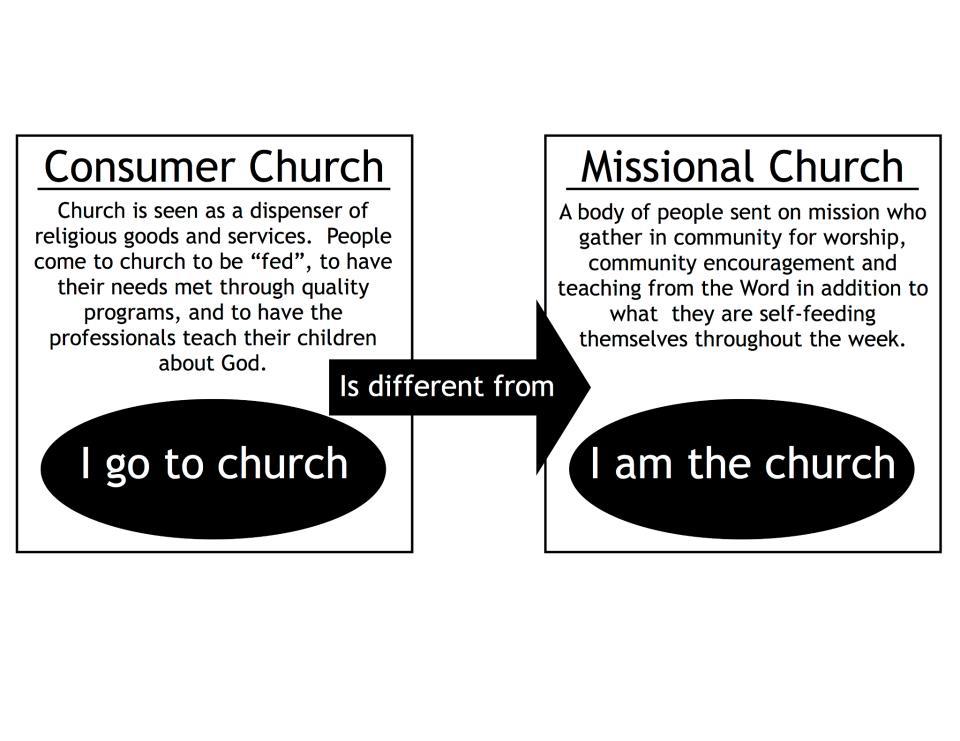

The most thoughtful members of the Seeker Friendly Service movement agree that the straight “seeker service” is not really worship, and therefore new believers are brought out of the seeker service into a weekly worship service for believers. The critics, on the other hand, generally see the worship service as the place for renewing and edifying believers who then go out into the world to do evangelism. The two models then, seem to be:

- Seeker service (evangelism) –> Worship service (edification)

- Worship service (edification) –> World (evangelism)

There are pragmatic problems with both models. The SFC model is financially very expensive, it is hard to assimilate new Christians out of seeker services into real worship services. And if the main worship service is very oriented toward seekers, the Christians often feel under-fed. On the other hand the critics cannot avoid the charge that they are not proposing any alternative to the current evangelistically ineffective church. One critic is very typical when he writes: “”While we [the seeker-friendly church] try to entice the world to come to church to hear the Gospel, the New Testament proclaims a powerful church worshipping God going out into the world in order to reach the lost (cf. The book of Acts.) True revivals have historically proved…that a revived and healthy church reaches a dying and lost world through its own awakened people.” This view says, “evangelism will take care of itself as long as we have great worship”. But the history of revivals also shows us innovations in outreach.

The Great Awakening was marked by two men who were remarkable innovators – George Whitefield in evangelism and John Wesley in organization. Many criticize seeker services because they are “not worship” and contain many elements of “entertainment”. Often they call us to look, instead at the revivals of the past. But they do not criticize George Whitefield for attracting huge crowds to his own “seeker programs”. He drew people into open air meetings with a kind of preaching that was unparalleled at the time in its popular appeal – his humor, his stories, his dramatically acted-out illustrations, and his astounding oratorical gifts drew tens of thousands. At the time he was labeled an “entertainer”. His meetings were not worship nor did they replace worship, but they were certainly critical to the revival. They provided Christians with a remarkable place to do friendship evangelism. His meetings were all over the city on virtually every day of the week. Whitefield’s evangelism was enormously aggressive and passionate. His preaching was racy and popular yet pointed toward the transcendent and holy God. Yet his public meetings shared many of the characteristics (and criticisms) of seeker services today.

Whitefield and Wesley did not become instruments of revival by simply being great expository preachers and renewing historic worship.

My main problem with the two models, however, is theological. They both assume that worship cannot be highly evangelistic. I want to show that this is a false premise. Churches would do best to make their “main course” an evangelistic worship service, supplemented by both a) numerous, variegated, creative, even daily (but not weekly) seeker-focused events, and b) intense meetings for Bible study and corporate prayer for revival and renewal.

Theological basis

God commanded Israel to invite the nations to join in declaring his glory. Zion is to be the center of world-winning worship. (Isaiah 2.2-4; 56.6-8) “Let this be written for a future generation, that a people not yet created may praise the Lord…so the name of the Lord will be declared in Zion, and his praise in Jerusalem when the peoples and the kingdoms assemble to worship the Lord”. (Psalm 102.18) Psalm 105 is a direct command to believers engage in evangelistic worship. The Psalmist challenges them to “make known among the nations what he has done” (v.1.) How? “Sing to him, sing praise to him; tell of his wonderful acts” (v.2) Thus believers are continually told to sing and praise God before the unbelieving nations. (See also Psalm 47.1; 100.1-5.) God is to be praised before all the nations, and as he is praised by his people, the nations are summoned and called to join in song.

Peter tells a Gentile church, “But you are a chosen people, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a people belonging to God, that you may declare the praises of him who called you out of darkness into his marvelous light.” (1 Peter 2.9) This shows us that the church is challenged to the same witness that Israel was called to – evangelistic worship. A key difference: in the Old Testament, the center of world-winning worship was Mt. Zion, but now, wherever we worship Jesus in spirit and in truth (John 4.21-26) we have come to the heavenly Zion. (Hebrews 12.18-24) In other words, the risen Lord now sends his people out singing his praises in mission, calling the nations to join both saints and angels in heavenly doxology. Jesus himself stands in the midst of the redeemed and leads us in the singing of God’s praises (Hebrews 2.12), even as God stands over his redeemed and sings over us in joy. (Zephaniah 3.17)

Biblical cases

1 Corinthians 14.24-25

Paul is addressing the misuse of the gift of tongues. He complains that tongues speaking will cause unbelievers to say they are out of their minds (v.23.) He insists that the worship service must be comprehensible to them. He says that if an unbeliever ” or unlearned one” (an uninitiated inquirer) comes in, and worship is being done “unto edification” , “he will be convinced by all that he is a sinner and will be judged by all” (v.24.) Of what does this conviction consist? “The secrets of his heart will be laid bare” (v.25.) It may mean he realizes that the worshippers around him are finding in God what his heart had been secretly searching for, but in the wrong ways. It may mean the worship shows him how his heart works. The result: “so falling on his face, he will worship God, exclaiming, ‘God is really among you’” (v.25.)

Acts 2

When the Spirit falls on those in the upper room, a crowd gathers (v.5) because a) they are hearing the disciples praising God (“we hear them declaring the wonders of God” v.11), an d b) and also because this worship is “in our own tongues” (v.11.) As a result, they are first made very interested (“amazed and perplexed they asked one another, ‘what does this mean’” v.11), and later they are convicted deeply (“they were cut to the heart and said…’Brethren, what shall we do?’” v.37.)

Comparison

There are obvious differences between the two situations. 1 Corinthians 14 pictures conversion happening on the spot (which is certainly possible.) In Acts 2 the non-believers are shaken out of their indifference (v.12), but the actual conversions (v.37-41) occurred at the end of an “after meeting” in which Peter explained the gospel (v.14-36) and showed them how to individually receive Christ (v.38-39.) It is often pointed out that the tongues in the two situations are different. But students usually are looking so carefully at what the two passages teach about tongues and prophecy that they fail to note what they teach about worship and evangelism. We can learn this:

1. Non-believers are expected to be present in Christian worship. In Acts 2 it happens by word-of-mouth excitement. In 1 Corinthians 14 it is probably the result of personal invitation by Christian friends. But Paul in 14.23 expects both “unbelievers” and “the unlearned” (literally “a seeker”– “one who does not understand”) to be present in worship.

2. Non-believers must find the praise of Christians to be comprehensible. In Acts 2 it happens by miraculous divine intervention. In I Corinthians 14 it happens by human design and effort. But it cannot be missed that Paul directly tells a local congregation to adapt its worship because of the presence of unbelievers. It is a false dichotomy to insist that if we are seeking to please God we must not ask what the un-churched feel or think about our worship.

3. Non-believers can fall under conviction and be converted through comprehensible worship. In 1 Cor 14 it happens during the service, but in Acts 2 it is supplemented by “after meetings” and follow-up evangelism. God wants the world to overhear us worshipping him. God directs his people not to simply worship, but to sing his praises “before the nations.” We are not to simply communicate the gospel to them, but celebrate the gospel before them.

Three practical tasks

2. Getting unbelievers into worship.

The numbering is not a mistake. This task is actually comes second, but nearly everyone thinks it come first! It is natural to believe that they must get non-Christians into worship before they can begin “doxological evangelism”. But the reverse is the case. Non-Christians do not get invited into worship unless the worship is already evangelistic. The only way they will have non-Christians in attendance is through personal invitation by Christians. Just as in the Psalms, the “nations” must be directly asked to come. But the main stimulus to building bridges and invitation is the comprehensibility and quality of the worship experience.

Christians will instantly sense if a worship experience will be attractive to their non-Christian friends. They may find a particular service wonderfully edifying for them, and yet know that their non-believing neighbors would react negatively. Therefore, a vicious cycle persists. Pastors see only Christians present, so they lack incentive to make their worship comprehensible to outsiders. But since they fail to make the adaptations, Christians who are there (though perhaps edified themselves) do not think to bring their skeptical and non-Christian friends to church. They do not think they will be impressed. So no outsiders come. And so the pastors respond only to the Christian audience. And so on and on. Therefore, the best way to get Christians to bring non-Christians is to worship as if there are dozens and hundreds of skeptical onlookers. And if you worship as if, eventually they will be there in reality.

1. Making worship comprehensible to unbelievers.

Our purpose is not to make the unbeliever “comfortable”. (In 1 Corinthians. 14.24-25 or Acts 2:12 and 37 – they are cut to the heart!) We aim to be intelligible to them. We must address their “heart secrets” (1 Corinthians 14.25) That means we must remember what it is like to not believe; we must remember what an unbelieving heart is like. How do we do that?

a) Worship and preaching in the “vernacular”. It is hard to overstate how ghetto-ized our preaching is. It is normal to make all kinds of statements that appear persuasive to us but are based upon all sorts of premises that the secular person does not hold. It is normal to make all sorts of references using terms and phrases that mean nothing outside or our Christian sub-group. So avoid unnecessary theological or evangelical sub-culture “jargon”, and explain carefully the basic theological concepts, such as confession of sin, praise, thanksgiving, and so on. In the preaching, showing continual willingness to address the questions that the unbelieving heart will ask. Speak respectfully and sympathetically to people who have difficulty with Christianity. As you write the sermon, imagine an particular skeptical non-Christian in the chair listening to you. Add the asides, the qualifiers, the extra explanations necessary. Listen to everything said in the worship service with the ears of someone who has doubts or troubles with belief.

b) Explain the service as you go along. Though there is danger of pastoral verbosity, learn to give 1 or 2 sentence, non-jargony explanations of each new part of the service. “When we confess our sins, we are not groveling in guilt, but dealing with our guilt. If you deny your sins you will never get free from them.” It is good to begin worship services as the Black church often does, with a “devotional”– a brief talk that explains the meaning of worship. This way you continually instruct newcomers in worship.

c) Directly address and welcome them. Talk regularly to “those of you who aren’t sure you believe this, or who aren’t sure just what you believe.” Give them many asides, even expressing the language of their hearts. Articulate their objections to Christian living and belief better than they can do it themselves. Express sincere sympathy for their difficulties, even when challenging them severely for their selfishness and unbelief. Admonish with tears (literally or figuratively.) Always grant whatever degree of merit their objections have. It is extremely important that the unbeliever feel you understand them. “I’ve tried it before and it did not work.” “I don’t see how my life could be the result of the plan of a loving God.” “Christianity is a straightjacket.” “It can’t be wrong if it feels so right.” “I could never keep it up.” “I don’t feel worthy; I am too bad.” “I just can’t believe.”

d) Quality aesthetics. The power of art draws people to behold it. Good art and its message enters the soul through the imagination and begins to appeal to the reason, for art makes ideas plausible. The quality of music and speech in worship will have a major impact on its evangelistic power. In many churches, the quality of the music is mediocre or poor, but it does not disturb the faithful. Why? Their faith makes the words of the hymn or the song meaningful despite its artistically poor expression, and further, they usually have a personal relationship with the music-presenter. But any outsider who comes in, who is not convinced of the truth and who does not have any relationship to the presenter, will be bored or irritated by the poor offering. In other words, excellent aesthetics includes outsiders, while mediocre or poor aesthetics exclude. The low level of artistic quality in many churches guarantees that only insiders will continue to come. For the non-Christian, the attraction of good art will have a major part in drawing them in.

e) Celebrate deeds of mercy and justice. We live in a time when public esteem of the church is plummeting. For many outsiders or inquirers, the deeds of the church will be far more important than words in gaining plausibility. The leaders of most towns see “word-only” churches as costs to their community, not a value. Effective churches will be so involved in deeds of mercy and justice that outsiders will say, “we cannot do without churches like this. This church is channeling so much value into our community through its services to people that if it went out of business, we’d have to raise everybody’s taxes.” Mercy deeds give the gospel words plausibility (Acts 4.32 followed by v.33.) Therefore, evangelistic worship services should highlight offerings for deed ministry and should celebrate through reports and testimonies and prayer what is being done. It is best that offerings for mercy ministry be separate, attached (as traditional) to the Lord’s Supper. This brings before the non-Christian the impact of the gospel on people’s hearts (it makes us generous) and the impact of lives poured out for the world.

f) Present the sacraments so as to make the gospel clear. Baptism, and especially adult baptism, should be made a much more significant event if worship is to be evangelistic. There may need to be opportunity for the baptized to offer personal testimony as well as assent to questions. The meaning of baptism should be made clear. A moving, joyous, personal charge to the baptized (and to all baptized Christians present) should be made. In addition, the Lord’s Supper can become a converting ordinance. If it is explained properly, the unbeliever will have a very specific and visible way to see the difference between walking with Christ and living for oneself. The Lord’s Supper will confront every individual with the question: “are you right with God today? now?” There is no more effective way to help a person to do a spiritual inventory. Many seekers in U.S. churches will only realize they are not Christians during the fencing of the table after an effective sermon on the meaning of the gospel. (See below for more on addressing unbelievers during communion.)

g) Preach grace. The one message that both believers and unbelievers need to hear is that salvation and adoption are by grace alone. A worship service that focuses too much and too often on educating Christians in the details of theology will simply bore or confuse the unbelievers present. For example, a sermon on abortion will generally assume the listener believes in the authority of the word and the authority of Jesus, and does not believe in individual moral autonomy. In other words, abortion is “doctrine D”, and it is based on “doctrines A, B, and C.” Therefore, people who don’t believe or understand doctrines ABC will find such a sermon un-convicting and even alienating. This does not mean we should not preach the whole counsel of God, but we must major on the “ABC’s” of the Christian faith. If the response to this is “then Christians will be bored”, it shows a misunderstanding of the gospel. The gospel of free, gracious justification and adoption is not just the way we enter the kingdom, but also the way we grow into the likeness of Christ. Titus 2.11-13 tells us how it is the original, saving message of “grace alone” that consequently leads us to sanctified living: “For the grace of God that brings salvation has appeared to all men. It teaches us to say ‘no’ to ungodliness and worldly passions, and to live self-controlled, upright and godly lives in the present age, while we wait for the blessed hope – the appearing of our great God and savior Jesus Christ.” Many Christians are “defeated” and stagnant in their growth because they try to be holy for wrong motives. They say “no” to temptation by telling themselves “God will get me” or “people will find out” or “I’ll hate myself in the morning” or “it will hurt my self-esteem” or “it will hurt other people” or “it’s against the law – I’ll be caught” or “it’s against my principles” or “I will look bad”. Some or all of these may be true, but Titus tells us they are inadequate. Only the grace of God, the logic of the gospel will work. Titus says it “teaches” us, it argues with us.

Therefore, the one basic message that both Christians and unbelievers need to hear is the gospel of grace. It can then be applied to both groups, right on the spot and directly. Sermons which are basically moralistic will only be applicable to either Christians OR non-Christians. But Christo-centric preaching, preaching the gospel both grows believers and challenges non-believers. If the Sunday service and sermon aim primarily at evangelism, it will bore the saints. If they aim primarily at education, they’ll bore and confuse unbelievers. If they aim at praising the God who saves by grace they’ll both instruct insiders and challenge outsiders.

3. Leading to commitment

We have seen that unbelievers in worship actually “close with Christ” in two basic ways. Some may come to Christ during the service itself. (1 Corinthians 14.24-25) Others must be “followed up” very specifically.

a) During the service. One major way to invite people to receive Christ during the service is as the Lord’s Supper is distributed. We say: “if you are not in a saving relationship with God through Christ today, do NOT take the bread and the cup, but, as they come around, take Christ. Receive him in your heart as those around you receive the food. Then immediately afterwards, come up here and tell an officer or a pastor about what you’ve done, so we can get you ready to receive the Supper the next time as a child of God.” Another way to invite commitment during the service is to give people a time of silence after the sermon. A “prayer of belief” could be prayed by the pastor (or printed in the bulletin at that juncture in the order of worship) to help people reach out to Christ. Sometimes it may be good to put a musical interlude or an offering after the sermon but before the final hymn. This affords people time to think and process what they have heard and offer themselves to God in prayer. If, however, the preacher ends his sermon, prays very briefly, and moves immediately into the final hymn, no time is given to people who are under conviction for offering up their hearts.

b) After meetings. Acts 2 seems to show us an “after meeting.” In v.12 and 13 we are told that some folks mocked upon hearing the apostles praise and preach, but others were disturbed and asked “what does this mean?” Then Peter very specifically explained the gospel, and, in response to a second question “what shall we do?” (v.37), explained very specifically how to become Christians. Historically, it has been found very effective to offer such meetings to unbelievers and seekers immediately after evangelistic worship. Convicted seekers have just come from being in the presence of God, and they are often most teachable and open. To seek to “get them into a small group” or even to merely return next Sunday is asking a lot of them. They may be also “amazed and perplexed” (Acts 2.12), and it is best to “strike while the iron is hot”. This is not to doubt that God is infallibly drawing his elect! That knowledge helps us to 16 relax as we do evangelism, knowing that conversions are not dependent on our eloquence. But the Westminster Confession tells us that God ordinarily works through secondary causes, normal social and psychological processes. Therefore, to invite people into a follow-up meeting immediately is usually more conducive to “conserving the fruit of the Word.”

After meetings may consist first of one or more persons who wait at the front of the auditorium to pray with and talk with any seekers who come forward to make inquiries right on the spot. A second after meeting can consist of a simple question-and-answer session with the preacher in some room near the main auditorium or even in the auditorium (after the postlude.) Third, after meetings should also consist of one or two classes or small group experiences targeted to specific questions non-Christians ask about the content, relevance, and credibility of the Christian faith. After meetings should be attended by skilled lay evangelists who can come alongside of newcomers and answer spiritual questions and provide guidance as to their next steps.

***

To download this paper in .pdf form, including footnotes: Click: Evangelistic Worship-Keller